Gas gouging

The American people hate a lot of things, but if there's one thing the people hate unequivocally and across all dividing lines, it's higher gas prices. Except, of course, the refiners, who love it. After all, they're the ones who pushed the price up.

Sounds like another anti-corporate conspiracy theory? Well maybe it is, but the signs are unmistakable - just drive over to your nearest gas station - and there doesn't seem to be any other explanation.

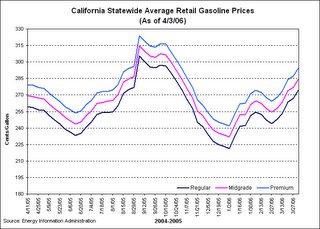

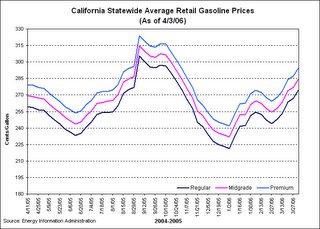

It's that time of year again. Gas prices are going up due to a dramatic weather phenomenon. No, it's not hurricane season yet: I am talking about the Summer. The time when people get out of their houses and drive all over this beautiful land. And, as always, gas prices are steadily rising. The CA average price has hit $3.00 already! And it looks set to go up, higher even than last year's peak at the time of Hurricane Katrina.

So why are they going up? Well, of course, oil prices are rising too. But the price of oil is only half the price of a gallon of gas. The rest is made up of taxes and refining costs. And, of course, we all know that Big Oil reported phenomenal profits in 2005, despite all the 'problems' it faced due to Katrina hitting its refineries on the Gulf Coast, and that ExxonMobil has now reclaimed its spot at the top of the Fortune 500 from Walmart.

A look at the linked graphic reveals that the contribution of refining costs to the total price of a gallon of gas is clearly higher now than it was earlier this year, or in previous summers (barring 2005). The oil companies claim this is because they are forced to produce lots of gas to meet the demand, despite the fact that some of their capacity is still offline after Katrina. The real question, then, is why do the refineries not have enough spare capacity to make up for losses due to natural calamities or other unforeseen events? Here's a fact: no new refineries have been built in the USA in the last 25 years. It's obvious that the oil companies have invested very little or no money in expanding capacity or building new refineries in the face of rising demand. Their strategy has, instead, been to raise gas prices to recover their operating costs and more - which explains the soaring profits. Why must the people pay for the lack of foresight or sound business planning on the part of Big Oil?

Some of the other reasons for high prices being proferred by Big Oil border on the absurd: one, that there is 'instability' in the Middle East (like there isn't always) and two, that there are additional costs due to supply and storage problems associated with ethanol additives.

Big Oil is not solely responsible for the gas prices we are seeing today. The US Government has been very reluctant about enforcing effective measures to decrease gas consumption, and despite the wave of hybrids and high-mileage cars hitting the market, gas-guzzling SUVs and trucks are still very popular. Old habits die hard.

Condemnation of Big Oil and its greedy profit-first policies are, however, coming from all quarters. Members of Congress, including Sen. Byron L. Dorgan (D-N.D.), a member of both the Senate Commerce and Energy committees, and Sen. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) are pointing fingers at the oil companies for gas price gouging. Further, Jason Vines, vice president of communications at DaimlerChrysler, has expressed his indignation at Big Auto still taking the flak for driving America (literally) to oil dependency while Big Oil rakes in the moolah. This inspite of the auto majors having revamped their lineup, now offering many higher-mileage cars equipped with new fuel-saving technologies. I have to agree with him - it does seem like the auto majors are trying hard to produce and sell frugal cars.

But at $3 a gallon (or more), can any car be frugal enough?

Sounds like another anti-corporate conspiracy theory? Well maybe it is, but the signs are unmistakable - just drive over to your nearest gas station - and there doesn't seem to be any other explanation.

It's that time of year again. Gas prices are going up due to a dramatic weather phenomenon. No, it's not hurricane season yet: I am talking about the Summer. The time when people get out of their houses and drive all over this beautiful land. And, as always, gas prices are steadily rising. The CA average price has hit $3.00 already! And it looks set to go up, higher even than last year's peak at the time of Hurricane Katrina.

So why are they going up? Well, of course, oil prices are rising too. But the price of oil is only half the price of a gallon of gas. The rest is made up of taxes and refining costs. And, of course, we all know that Big Oil reported phenomenal profits in 2005, despite all the 'problems' it faced due to Katrina hitting its refineries on the Gulf Coast, and that ExxonMobil has now reclaimed its spot at the top of the Fortune 500 from Walmart.

A look at the linked graphic reveals that the contribution of refining costs to the total price of a gallon of gas is clearly higher now than it was earlier this year, or in previous summers (barring 2005). The oil companies claim this is because they are forced to produce lots of gas to meet the demand, despite the fact that some of their capacity is still offline after Katrina. The real question, then, is why do the refineries not have enough spare capacity to make up for losses due to natural calamities or other unforeseen events? Here's a fact: no new refineries have been built in the USA in the last 25 years. It's obvious that the oil companies have invested very little or no money in expanding capacity or building new refineries in the face of rising demand. Their strategy has, instead, been to raise gas prices to recover their operating costs and more - which explains the soaring profits. Why must the people pay for the lack of foresight or sound business planning on the part of Big Oil?

Some of the other reasons for high prices being proferred by Big Oil border on the absurd: one, that there is 'instability' in the Middle East (like there isn't always) and two, that there are additional costs due to supply and storage problems associated with ethanol additives.

Big Oil is not solely responsible for the gas prices we are seeing today. The US Government has been very reluctant about enforcing effective measures to decrease gas consumption, and despite the wave of hybrids and high-mileage cars hitting the market, gas-guzzling SUVs and trucks are still very popular. Old habits die hard.

Condemnation of Big Oil and its greedy profit-first policies are, however, coming from all quarters. Members of Congress, including Sen. Byron L. Dorgan (D-N.D.), a member of both the Senate Commerce and Energy committees, and Sen. Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) are pointing fingers at the oil companies for gas price gouging. Further, Jason Vines, vice president of communications at DaimlerChrysler, has expressed his indignation at Big Auto still taking the flak for driving America (literally) to oil dependency while Big Oil rakes in the moolah. This inspite of the auto majors having revamped their lineup, now offering many higher-mileage cars equipped with new fuel-saving technologies. I have to agree with him - it does seem like the auto majors are trying hard to produce and sell frugal cars.

But at $3 a gallon (or more), can any car be frugal enough?